#MeToo and #TimesUp protests about the treatment of women in the workplace have brought renewed attention to gender pay equity. This brief looks at three legislative solutions that aim to close the gap by increasing pay transparency and pushing employers to set salaries to the position, not the history of the person doing the job.

Overview

Despite a long history of legislation aimed at preventing employers from paying women less than men for the same work, a gender wage gap prevails in the United States. In recent years, state policymakers have strengthened efforts to eliminate the gender pay gap, focusing on three approaches:

- Laws that prohibit employers from enforcing pay secrecy (CA, CO, IL, LA, ME, MI, MN, NH, NJ, VT)1

- Laws that ban employers from asking potential hires about past earnings (CA, DE, MA, OR; the cities of Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, New Orleans, and New York)2

- Laws that require employers to report gender wage gap data (AK, IL, MN, NH)3

By increasing pay transparency and banning employers from asking about previous pay, lawmakers hope to undo discriminatory hiring and pay practices.

The problem

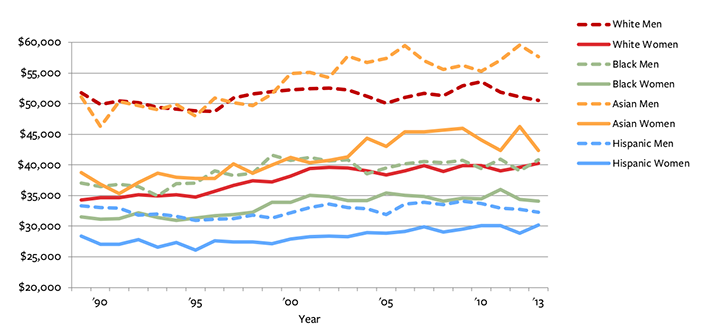

Women are paid less money for the same work: In the U.S. today, women who work full time make 80 cents, on average, for every dollar that white men make. The Economic Policy Institute shows that this wage gap also varies significantly by race:4 Asian women earn 90 cents on the dollar, white women 81 cents, black women 65 cents, and Hispanic women only 58 cents on the dollar in comparison to white men. Wage differences are starkest among high-income earners, with women only making 74 cents on the dollar compared to their male counterparts.

The wage gap persists across education levels and occupations: Despite the hope that women’s educational attainment might level the playing field in earning power, education does not appear to make a difference; women are paid less at every education level in comparison to men.5

The Institute for Women’s Policy Research shows that women earn less than men in nearly all occupations, whether it is work predominantly performed by women or men.6 For example, even in a female-dominated field like education, female elementary and middle school teachers make only 87 percent of what a man makes for performing the same job. In male-dominated fields like financial management, women earn roughly 70 percent of what men earn for the same work.

The wage gap has long-term economic impacts: Pay discrimination is pervasive in American culture, and has steep economic consequences. According to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, a typical woman who worked full time and year round would lose out on roughly a half million dollars over her lifetime, compared to her male counterpart. A college-educated woman would lose even more: roughly $800,000 over her lifetime.7

Why the wage gap persists: There are several possible explanations for the persistence of the gender wage gap: 1. Women may be more likely to choose lower-paying occupations or positions (such as preschool teacher versus high school teacher); 2. Women are more likely to reduce or leave paid work in order to care-take for children, thus reducing their earnings and slowing career advancement; 3. Employers’ pay setting is affected by gender bias and discrimination; and 4. Women are less aggressive in negotiating over pay (or women’s assertiveness is less likely to be successful).8 This brief focuses on policies that seek to level the playing field in pay negotiation, by increasing transparency and pushing employers to set pay according to the job, not the person.

1. Don’t prohibit workers from discussing pay

To counter pervasive gender bias, state policymakers in several states have passed laws banning pay secrecy. Pay secrecy prevails when companies prohibit employees from openly discussing pay with colleagues. This secrecy enables wage gaps to persist.

Figure 1. The gender and race wage gap: Median annual earnings for full-time workers

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements

Pay secrecy is considered illegal under Section 7 of the federal National Labor Relations Act, which protects non-supervisory employees from employer retaliation if they choose to discuss wages with colleagues.9 However, a 2010 survey found that 66 percent of private-sector workers and 15 percent of public-sector workers were either formally or informally prohibited by their employers from discussing pay with colleagues.10 Often, employers include formal prohibitions on sharing wage information in employee handbooks. Employers may also encourage a culture of pay secrecy by discouraging wage sharing, or handing out paychecks in private.11 Social norms in the U.S. may also hold employees back from inquiring about others’ earnings.12 Without feeling free to inquire about how much comparable colleagues are earning, women may not even know that they are making less than their male counterparts, and thus are unlikely to raise complaints or ask for comparable salaries.

Starting in the 1980s, Michigan (1982) and California (1984) adopted pay secrecy laws to prohibit employers from discriminating against employees who ask about salaries in the workplace. The consequences imposed by such laws vary by state, but the general intent is to protect workers’ rights to share and discuss information about employee salaries. In a paper published in IRLE’s journal, Industrial Relations, Marlene Kim investigates the effects of state pay secrecy laws. Kim (Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts, Boston) compares earnings in six states that had banned pay secrecy before 2012 to earnings in states that had not. Using a regression method13 to construct a comparison that controls for other factors (e.g., worker demographics and regional wage differences), Kim finds that women’s earnings are 3 percent higher in states that have outlawed pay secrecy. She also finds that in states with such policies, the gender wage gap is reduced by as much as 12 to 15 percent for workers with a college degree, and by 6 to 8 percent for workers without. This finding lends considerable support for adopting such prohibitions in order to close the gender wage gap.

Federal reform failure

Despite evidence that such reform will reduce pay inequity, efforts to introduce similar worker protections at the federal level have been unsuccessful. Kim notes that over 20 attempts have been made to amend the Fair Labor Standards Act, all of which have stalled or been voted down. Such legislation (like the Paycheck Fairness Act) would have increased penalties against employers that enforce pay secrecy and strengthened remedies for employees. More progress has been made at the state level. In 2016, California, Delaware, Maryland, and Connecticut strengthened their state-level pay secrecy laws.14 As of 2017, 18 states now have laws on the books to bar employers from discriminating or retaliating against employees who inquire about wages.15

2. Don’t base employee pay on salary history

Equal pay advocates posit that unfair cultural practices have evolved in the salary negotiation process to perpetuate pay inequities for women. One such practice is when employers ask potential hires about salaries earned at prior jobs during negotiations. Since women tend to earn less in nearly all occupations in comparison to men,16 the practice of being asked to disclose one’s previous salary can compound inequalities and follow a woman over the course of her career.

IRLE faculty affiliate Laura Kray, Professor at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, studies the role of gender in negotiations. In a literature review of empirical research on the topic,17 Kray and co-author Jessica Kennedy report that men and women alike typically stereotype women as poor negotiators. The authors find that cultural biases privilege men in negotiations, since they are more likely to display characteristics associated with masculinity, such as assertiveness, strength, and competition, that benefit them in discussions about pay. Women who act assertively and display “masculine” traits during negotiations may be viewed unfavorably by employers who perceive such qualities as too aggressive. As a result, women may be more apprehensive about the negotiation process than men and may be more likely to fall into feminine stereotype traps and settle for lower wages,18 compounding a vicious cycle of gender pay discrimination.

Banning salary history questions from the negotiation process would reduce the likelihood that women would have to negotiate from a lower starting point than male counterparts. In other words, banning the question makes it possible for women to enter into negotiations on level footing with men. In recent attempts to fight pay disparities from following a woman over the course of her career, a wave of state and city reforms were enacted during 2016 and 2017 that ban employers from asking job candidates their salaries from previous jobs. California, Delaware, Massachusetts, and Oregon, along with the cities of New Orleans, New York City, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh, now have such bans.19

The idea that the negotiation process itself is to blame for gender pay disparities suggests other possible remedies. For example, the CEO of Reddit has banned salary negotiations at her company altogether. And while Massachusetts has banned the salary history question, the state now also requires employers to publish salary ranges based on the skills and qualifications needed for the job, which provides transparency for the negotiation process.20

3. Make salaries public

Other states and companies are also increasing salary transparency to reduce the gender wage gap. The logic of salary transparency is straightforward: when employees have access to information about on what their co-workers earn, and pay gaps at specific employers are exposed, employers will be pressured to fix pay disparities.

States like Alaska, Illinois, Minnesota, and New Hampshire already collect and publish data on the pay gap. 21 However, data transparency proposals have recently received pushback. In 2017, California Governor Jerry Brown vetoed AB 1209, the Gender Pay Gap Transparency Act, in a state with one of the strongest equal pay environments in the country. The vetoed bill would have required companies with more than 500 employees to collect and report salary information for men and women in the same job to the state, which would then be published online.22 At the federal level, President Trump suspended an Executive Order put in place by President Obama that would have advanced pay transparency for federal contract employees.23 The Executive Order would have required companies to report salaries by race and gender.

In the short term, company efforts to increase salary transparency may outpace government action. For example, companies like Amazon, Apple, and Gap have recently conducted internal audits of their employee pay data.24 Moreover, just last year, investors like Arjuna Capital urged several tech companies to publish the pay gap between male and female employees, and will continue pushing banks they work with to do the same.25 When corporations lead the way to resolving gender pay inequalities, this can be appealing to potential employees. In another study co-authored by Kray, the authors find that undergraduate business students—especially women—would rather work for companies that prioritize fairness and ethical business practices.26

Conclusions and further inquiry

After several decades of documented gender pay inequality, there is a growing call for policymakers to do something about it. Despite strong evidence that the policies described here will be effective, any progress on closing the gender wage gap is likely to remain at the state and local level, or within the corporate sector, for the time being. Indirect policy routes can be pursued as well. Research conducted by the Obama administration found that minimum wage increases present a significant opportunity for promoting equal pay for women, especially for those at the bottom end of the income distribution.27 Women are more likely to be concentrated in occupations that pay the minimum wage and in tipped occupations.28 Family-friendly policies, such as paid family and medical leave, affordable child care, and early childhood education programs coupled with equal pay policies could significantly reduce the gender wage gap while helping single mothers with children.29 These are all policies on which states such as California have already taken the lead in the absence of federal action.

This brief draws on research by IRLE faculty affiliate and UC Berkeley Professor Laura Kray on gender discrimination in pay negotiations, and research on pay secrecy laws by Professor Marlene Kim published in IRLE’s academic journal: Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society

Author: Erin Coghlan, a doctoral candidate at the Graduate School of Education at UC Berkeley. Series editor: Sara Hinkley, Associate Director of the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment.

FEATURED RESEARCH

Jessica A. Kennedy & Laura J. Kray (2015). A pawn in someone else’s game? The cognitive, motivational, and paradigmatic barriers to women’s excelling in negotiation. Research in Organizational Behavior, 34, 3-28.

Marlene Kim (2015). Pay secrecy and the gender wage gap in the United States. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 54(4), 648-667.

References

- States vary in terms of which employees are covered, and under which circumstances. For example, not all states cover both public and private employers, and not all states protect supervisors and managers as well as employees. Moreover, in states like Illinois, New Jersey, and Maine, pay secrecy is prohibited in Equal Employment laws, but only when employees are investigating unequal pay claims. For more information see: Kim, M. (2015). Pay secrecy and the gender wage gap in the United states. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 54(4), 648-667 and Women’s Bureau, U.S. Department of Labor (2014). Fact sheet: Pay secrecy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor. Retrieved January 15, 2018, from https://www.dol.gov/wb/media/pay_secrecy.pdf

- New Orleans and Pittsburgh only cover public employers. All other states, cities, and Puerto Rico cover both public and private employers. For more information see: Cain, A. & Pelisson, A. (October 26, 2017). 9 places where people may never have to answer the dreaded salary question again. Business Insider. Retrieved January 15, 2018, from https://www.businessinsider.in/9-places-where-people-may-never-have-to-answer-the-dreaded-salary-question-again/

- States may vary in whether they collect data from public or private employers. For more information, see: Nielson, K. (2018). AAUW policy guide to equal pay in the states. Washington, DC: AAUW. https://www.aauw.org/resource/state-equal-pay-laws/

- Gould, E., Schieder, J. & Geier, K. (2016). What is the gender pay gap and is it real? Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/files/pdf/112962.pdf

- Miller, K. (2018). The simple truth about the gender pay gap report. Washington, DC: American Association of University Women. https://www.aauw.org/research/the-simple-truth-about-the-gender-pay-gap/

- Hegewisch, A. & Williams-Baron, E. (2017). The gender wage gap by occupation 2016; and by race and ethnicity. Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research. https://iwpr.org/iwpr-general/the-gender-wage-gap-by-occupation-2016-and-by-race-and-ethnicity/

- Institute for Women’s Policy Research. (2016). Status of women in the United States (online database). https://statusofwomendata.org/explore-the-data/employment-and-earnings/employment-and-earnings/

- For example, see: Kennedy, J. A. & Kray, L. J. (2015). A pawn in someone else’s game? The cognitive, motivational, and paradigmatic barriers to women’s excelling in negotiation. Research in Organizational Behavior, 34, 3-28; and Women’s Bureau, U.S. Department of Labor (2017). Issue brief: Women’s earnings and the wage gap. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor. Retrieved February 20, 2018, from https://www.dol.gov/wb/resources/Womens_Earnings_and_the_Wage_Gap_17.pdf

- Kim, M. (2015).

- Institute for Women’s Policy Research (2017). Private sector workers lack pay transparency: Pay secrecy may reduce women’s bargaining power and contribute to gender wage gap. Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research. https://iwpr.org/publications/private-sector-pay-secrecy/

- Kim, M. (2015).

- Colella, A., Paetzold, R. L., Zardkoohi, A., Wesson, M. J. (2007). Exposing pay secrecy. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 55-71.

- Kim (2015) uses a difference-in-difference-in-difference (DDD) human capital wage regression model. The model controls for variables such as education levels, work experience, marital status, region of residence (metropolitan or central city) race, and ethnicity. This model is used to examine the effect of policy changes on women’s earnings.

- Zoppo, A., & Petulla, S. (2017). See what your state is doing to close the gender wage gap. NBC News. Retrieved December 15, 2017, from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/see-what-your-state-doing-close-wage-gap-n741351

- Nielson, K. (2018). AAUW policy guide to equal pay in the states. Washington, DC: AAUW. https://www.aauw.org/resource/state-equal-pay-laws/

- Hegewisch, A., Williams-Baron, E. (2017).

- Kennedy, J.A., & Kray, L.J. (2015).

- Kray, L.J., & Gelfand, M.J. (2009). Relief versus regret: The effect of gender and negotiating norm ambiguity on reactions to having one’s first offer accepted. Social Cognition, 27, 418-436.

- Cain, A. & Pelisson, A. (2017)

- See the following: Chandler, M. A. (2016). More state, city lawmakers say salary history requirements should be banned. The Washington Post. Retrieved December 15, 2017, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/social-issues/more-state-city-lawmakers-say-salary-history-requirements-should-be-bannedadvocates-for-women-argue-that-the-practice-contributes-to-the-nations-pay-gap/2016/11/14/26cb4366-90be-11e6-9c52-0b10449e33c4_story.html and Kray, L. (2015). The best way to eliminate the gender pay gap? Ban salary negotiations. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2015/05/21/the-best-way-to-way-to-eliminate-the-gender-pay-gap-ban-salary-negotiations/

- Nielson, K. (2018).

- Goodwin, K. (2017). California Governor vetoes two bills related to public report of gender wage differentials and discrimination based on “reproductive health decisions.” Labor & Employment Law Blog. https://www.laboremploymentlawblog.com/2017/10/articles/california-employment-legislation/cagovernor-vetoes-reproductive-health-decisions/

- Paquette, D. (2017). Trump administration halts Obama-era rule to shrink the gender wage gap. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/08/30/the-trump-administration-just-halted-this-obama-era-rule-to-shrink-the-gender-wage-gap/

- Raghu, M., & Lowell, C. (2017). Employer leadership to advance equal pay: Examples of promising practices. Washington, DC: National Women’s Law Center. https://nwlc.org/resources/employer-leadership-to-advance-equal-pay-examples-of-promising-practices/

- McGregor, J. (2017). The investor who pushed tech firms to publish their pay gap is going after big banks. The Washington Post. Retrieved December 15, 2017, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/

- Kennedy, J. A., Kray, L. J. (2014). Who is willing to sacrifice ethical values for money and social status?: Gender differences in reactions to ethical compromises. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(1), 52-59.

- National Economic Council, Council of Economic Advisers, the Domestic Policy Council, and the Department of Labor (2014). The impact of raising the minimum wage on women: And the importance of ensuring a robust tipped minimum wage. Washington, DC: The White House. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/20140325minimumwageandwomenreportfinal.pdf

- Allegretto, S. A. (2014). The impact of raising the minimum wage on women. Berkeley, CA: Institute for Research on Labor and Employment. http://irle.dream.press/the-impact-of-raising-the-minimum-wage-on-women/

- Kim, M. (2015).