Experiences in the Foster Care System

When considering the impact of parental substance use on childhood entries into foster care, it is important to identify the implications of a child entering foster care. When a child enters the foster care system due to parental inability to provide care, they are faced with a range of challenges for the duration of their time in foster care. Foster youth often experience multiple moves, school changes, caregiver changes, and instability in multiple areas of their life. As a result, the 23,000 foster youth who age out of the system each year experience disparate education and vocational outcomes.

Educational & Vocational Disparities for Former Foster Youth

About 23,000 youth will age out of the US foster care system this year. Little research has been done on foster youth who age out of the foster care system and begin to independently navigate their lives. When they leave the foster care system, many former foster youth do not yet have the training or life skills to effectively manage their own finances, medical care, or other areas of life that are essential tools to bridge their transition to adulthood.

As a result, foster youth experience disparities in educational outcomes compared to their peers. For example, former foster youth sometimes change schools at least once or twice a year while growing up, resulting in greater chances of falling behind. This impacts odds of completing high school and attending college.1

Additionally, of the former foster youth who go on to college, many lack the ability to seek advice and support from their parents or legal guardians for continued support. Former foster youth benefit from programs that provide support to meet their specific needs.

In terms of employment outcomes, research has shown that transition-age adolescents in the foster care system typically experience poor outcomes in terms of engagement and earnings in their careers. Lack of higher educational achievement is the main contributing factor for these difficulties. On average, foster youth earned $8,000 compared to a national average of $18,300 for their peers.2

One potential solution to improve former foster youth’s higher education and employment outcomes are Independent Living Programs (ILPs). An ILP is a federally funded program that assists current and former foster youth between the ages of 16 and 21 to achieve self-sufficiency prior to, and after, exiting the foster care system. Independent living programs that concentrate on the emotional dimensions of emancipation offer an important benefit to their participants, particularly if they are responsive to the cultural context of children and their families.3

Substance Use & Entries Into the Foster Care System

Considering that foster youth experience additional challenges compared to their peers, it is important to identify and remedy the causes of entries to the system in order to prevent additional children from needing to enter foster care and face these disparate outcomes later in life.

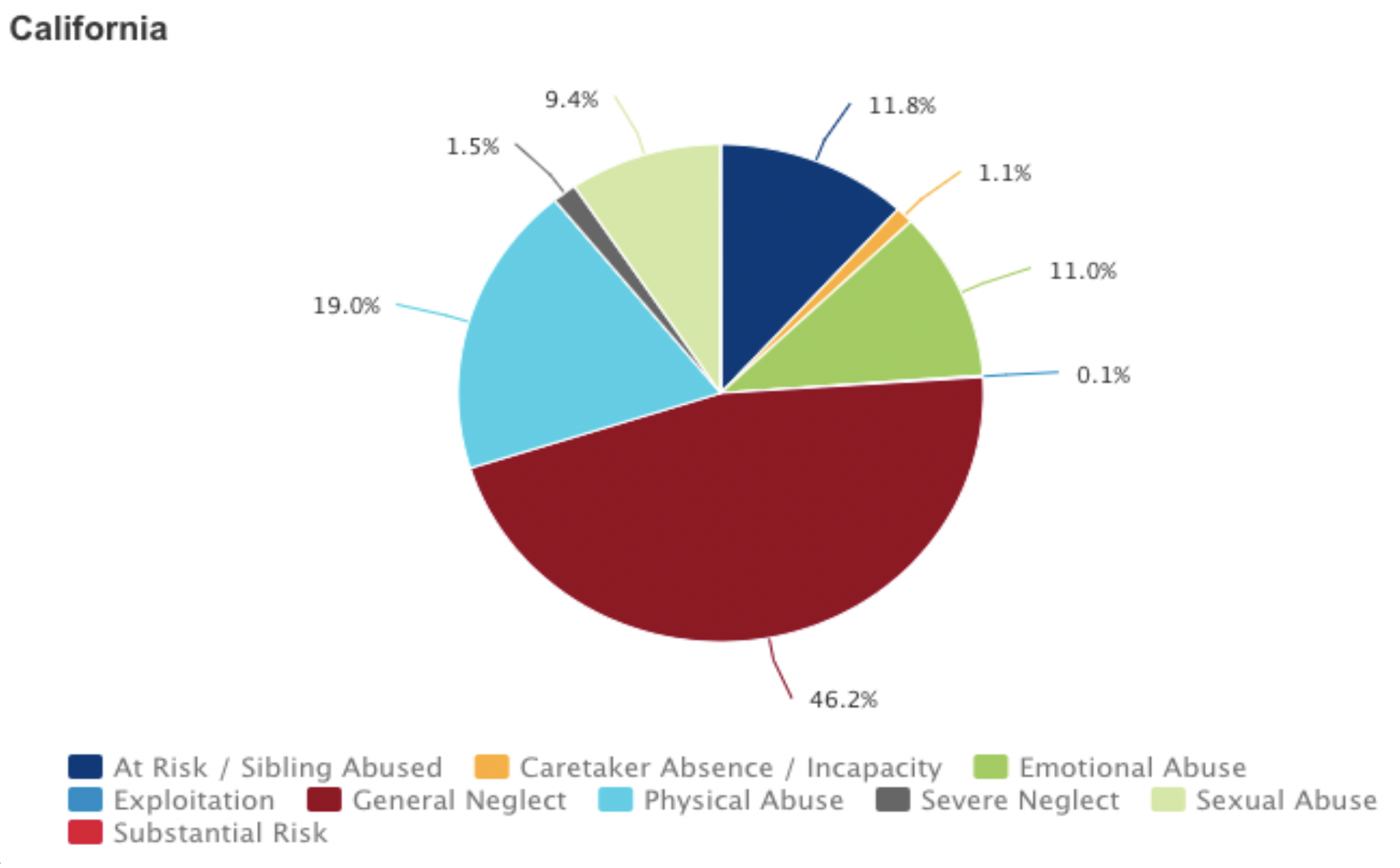

Children enter the child welfare system for a number of reasons, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, and other issues at home.

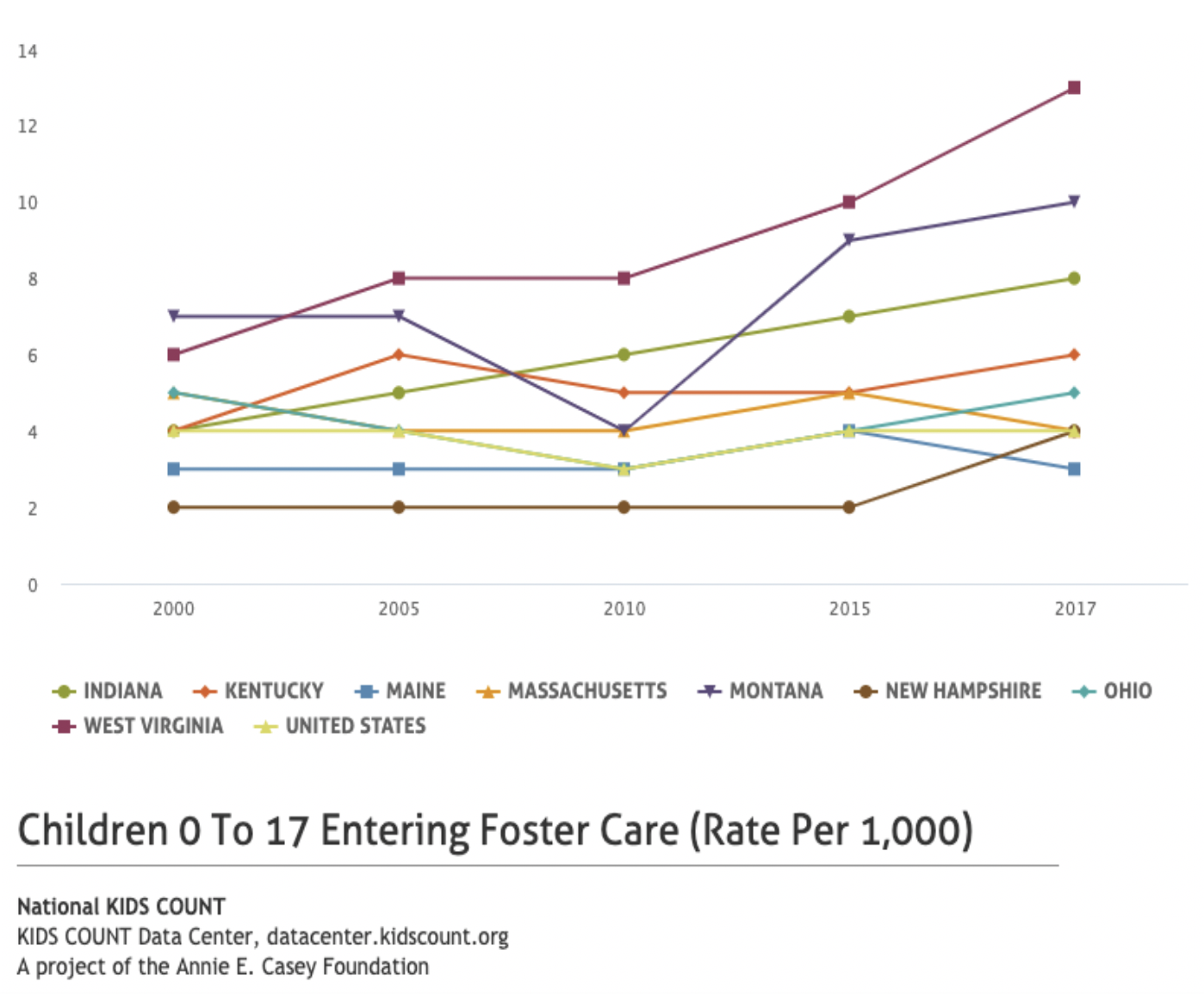

There was an increase in the number of children entering the foster system in 2017 (36%) because of parental drug use, compared with 15% in 2000.4 The percentage of children removed due to parental drug use increased almost 8% between 2009 and 2015; a larger increase than any other removal reason. 5

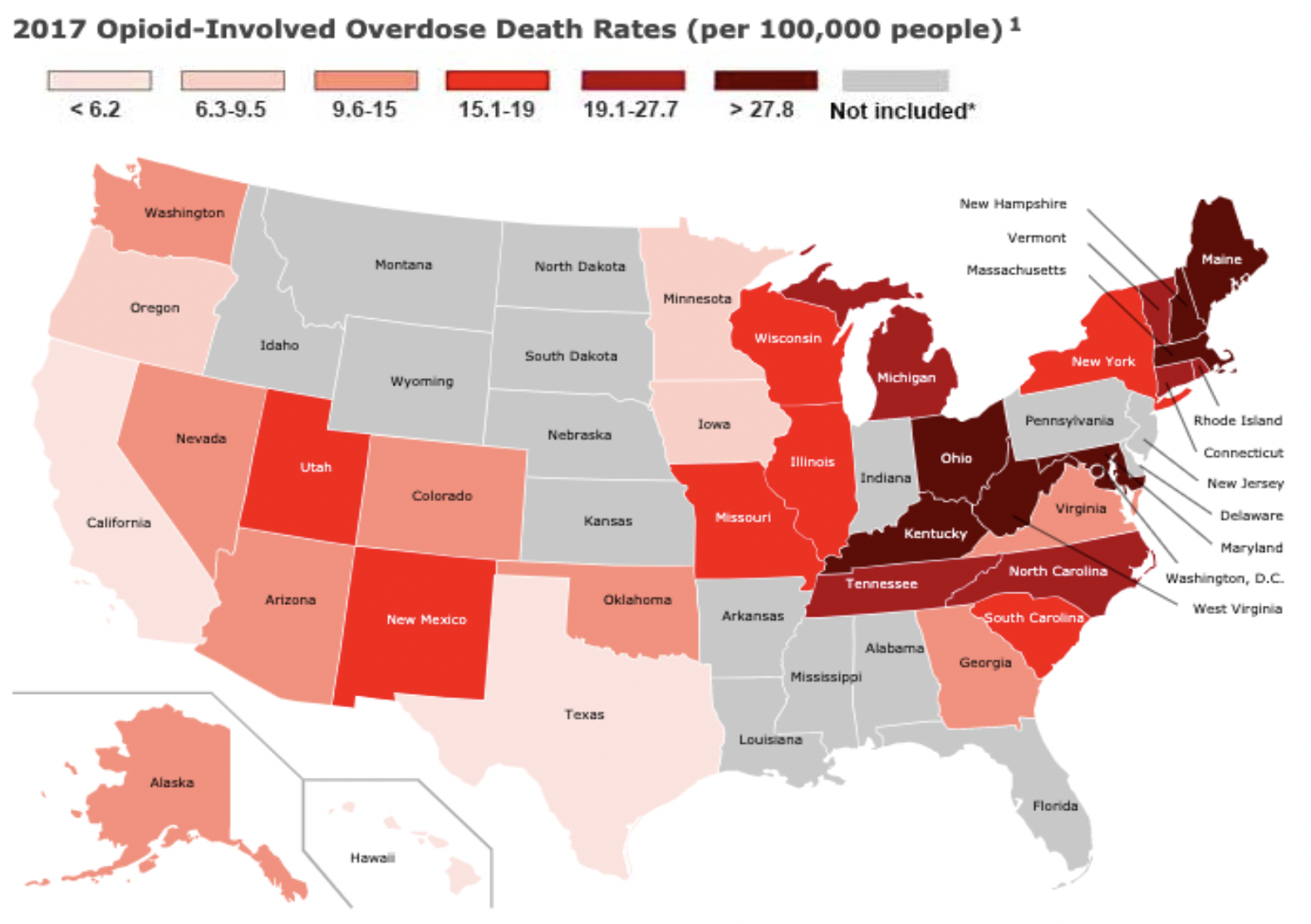

Parental opiate abuse has been found to be associated with these recent increases in entries to foster care. Opioid use-related deaths and number of foster care entries parallel each other in many counties and states. Starting in 2012, foster care entries began increasing alongside drug overdose death rates. In 2016, five out of six states with the highest rates of death from opioid overdoses had increases in foster care.6

Higher rates of overdose deaths and drug hospitalizations correspond with higher child welfare caseloads. In the average county, a 10% increase in any type of substance related hospitalization corresponded with about 2-3% increase in foster care entry rates.7

Children of parents who have opioid use issues are placed into the foster care system at a younger average age than those entering for other reasons. A recent epidemiological study linking birth, hospital discharge, and child protective data in California found that 61% of infants born with prenatal substance exposure in 2006 were reported to CPS before age 1.8

Between 2010 and 2015 the number of children under 4 in foster care grew 42% with the biggest increase for those under the age of 1, likely related to these removals of infants.9 When children are removed because of parental drug abuse, their periods away from home are typically longer, and the removal is less likely to result in reunification with the parent compared to removals for other reasons.10

Family First Prevention Services Act

One example of a support for families experiencing opiate or substance use issues who are at risk of child removal is a new federal law which provided additional child welfare funding. Some of this funding can be used for family services addressing mental health challenges, substance abuse, and offering in-home parent skill-based programs.

The two groups that are eligible for these new services are parents or relatives caring for those who are “candidates for foster care” and youth in foster care who are pregnant or already parents. State agencies can spend federal Title IV-E funds on prevention services for 12 months. The 12 months start the day that the child is identified in a “prevention plan” as a candidate for foster care or when they are listed on a prevention plan as being pregnant or parenting.

Family preservation services are short-term, family-focused services designed to assist families in crisis by improving parenting and family functioning while keeping children safe. For example, these funds could be used to assist families in accessing substance use treatment services to prevent the need for a child to be removed due to neglect. These initiatives may assist families in accessing needed resources to prevent child removal due to parental substance use.

Conclusions

Recent increases in the number of children removed from home due to parental substance use alongside the opioid epidemic in the US is concerning and increases in supports for families though new federal programs may be helpful in preventing further removals of children. There is a need for continued research and policy around ways to best support families with parents who are experiencing substance use issues, in order to stabilize families, decrease the number of children entering into the child welfare system, and improve long-term outcomes for children with parents experiencing substance use.

References

1 Ryan J. Davis (2006). College Access, Financial Aid, and College Success for Undergraduate from Foster Care, Pg 12 https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED543361.pdf

2 P.J. Pecora Children and youth services review (2006). National Foster Youth Institution

3 Scannapieco, M., Smith, M. & Blakeney-Strong, A. Transition from Foster Care to Independent Living: Ecological Predictors Associated with Outcomes. (2016). Child Adolesc Soc Work J 33, 293–302. https://doi-org.libproxy.berkeley.edu/10.1007/s10560-015-0426-0

4 Zill, N. (2011). Adoption from foster care: Aiding children while saving public money. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, Center on Children and Families.

5 Young, N. K. (2016). Written Testimony of Nancy K. Young, Ph.D.: Examining the Impact of the Opioid Epidemic. Lake Forest, CA: Children and Family Futures.

7 Radel, Laura, et al. “Substance Use, the Opioid Epidemic, and the Child Welfare System: Key Findings from a Mixed Methods Study.” (2018) 7 Mar. 2018, https://aspe.hhs.gov/aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/258836/SubstanceUseChildWelfareOverview.pdf.

8 Prindle, J., Hammond, I., & Putnam-Hornstein, E. (2018). Prenatal substance exposure diagnosed at birth and infant involvement with child protective services. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 75.

9 Children’s Bureau. (2017). The AFCARS Report: Preliminary FY 2017 Estimates. [Government Report]. Washington, D.C.: Government Reporting Office.