The last two years have seen the largest number of workers on strike since the late 1980s. Labor organizing has momentum, although its goals, structure, and tactics have fundamentally changed. IRLE faculty affiliate and UC Berkeley Professor of Law Catherine Fisk explains the new Alt-Labor movement, an increasingly popular form of worker solidarity characterized by activism, intervention, and advancing pro-worker legislation. She warns of a counter-revolution to the progress made by Alt-Labor, and suggests two legal changes that would promote the sustainability of labor movements in this new era: co-enforcement and the expansion of hiring halls.

Overview

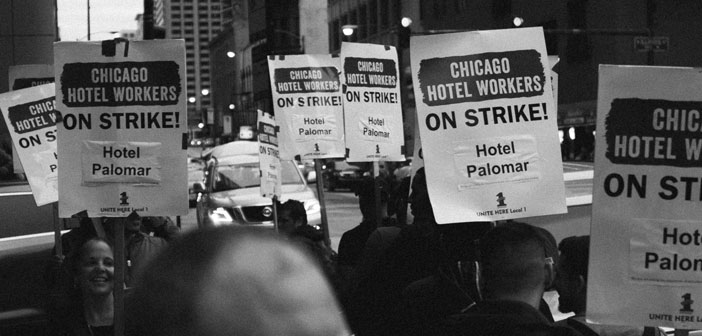

Over 485,000 workers went on strike in 2018, more than in any year since 1986, and the momentum was sustained in 2019.1 This jump in worker-led demonstrations can be attributed to the new activities of the labor movement called Alt-Labor. Alt-Labor refers to non-unionized workers who have been employing new forms of activism, intervention, and regulation. These workers notably organize outside the traditional confines of employer-based organizing. Alt-Labor often organizes by sector rather than employer, and they frequently focus on the passage and enforcement of minimum standards legislation in low-wage sectors. To build their engagement, Alt-Labor has relied on community based worker centers, unions, and associations of non-unionized workers. The COVID-19 crisis has further encouraged these new forms of organizing, with novel collaborations between state and local governments and community groups helping the unprecedented number of unemployed workers and essential workers.

Despite their effectiveness to date, these emerging forms of organizing require sustained activism, making it difficult to maintain momentum. There are two other challenges to this new form of organizing: (1) when movements succeed, there is often a judicial backlash that results in the loss of any gains made, and (2) the increased fissuring of work creates an environment of social exclusion, further making it difficult to organize workers.

In a new article from the Chicago-Kent Law Review, Catherine Fisk considers how recent Alt-Labor campaigns have sought to institutionalize gains. Based on the lessons learned from these case studies, she suggests two legal changes that will make Alt-Labor organizing more sustainable: co-enforcement and expansion of hiring halls.

Co-enforcement of labor laws

Fisk describes co-enforcement as the collaboration of labor standards agencies with worker centers and community groups to enforce labor law. Since worker centers and community groups have stronger networks with workers and are more culturally and linguistically competent, there will be improved compliance and enforcement when these organizations engage with workers and increase awareness of legal rights. Further, enforcement workers will be more effective because they will be better informed about the problems faced by low-wage employees. Creating a formal enforcement and governance role for these groups by funding and empowering them will also serve to support organizing efforts and encourage sustainability.

Successful examples of co-enforcement can be found in the San Francisco Office of Labor Standards Enforcement (OLSE) and the California Division of Labor Standards Enforcement (DLSE). In San Francisco, co-enforcement originated in 2006 when its minimum wage ordinance was amended. OLSE’s main contractor is the Chinese Progressive Association (CPA), which subcontracts with other community partners to ensure enforcement of standards outside of CPA’s cultural network. OLSE and community partner staff meet quarterly for progress updates and to discuss new developments in law or policy. The community partners are tasked with holding workshops, conducting outreach, and providing referral services that will educate workers and create the conditions in which workers would be more likely to report violations of labor law. One of the challenges of co-enforcement is the requirement for the contractor to provide deliverables that measure success. It is critical for agencies to recognize that getting to know an individual worker is a valuable use of time and resources but may not be reflected in the metrics that they are required to gather and report.

Another example that Fisk provides is the California DLSE’s Bureau of Field Enforcement (BOFE), which has a partnership with the California affiliate of the National Employment Law Project (NELP) and local worker organizations. NELP and the worker organizations identify and bring cases to BOFE, which then takes the lead on enforcement. For example, NELP first works with community groups to identify wage theft cases, the community groups then present these cases to BOFE, and BOFE prosecutes the case with assistance from the community group in lining up the case and building worker trust. Unlike OLSE, DLSE co-enforcement is privately funded which enables them to focus on worker organizing rather than metrics such as number of cases or trainings.

Fisk argues that not only does co-enforcement assist agencies in their task of enforcing labor laws, but it also brings funding, legitimacy, and power to worker organizations that can sustain them in this new era of organizing.

Hiring Halls

As a counter to employment agencies that charge high fees, do not provide benefits, and can lead to jobs that have no worker accountability, Fisk suggests bolstering hiring halls, both union and non-union, which give more power to workers. Hiring halls act as a facilitator between employers and employees in job matching, enable training and skill-building, and have the ability to administer a sectoral benefits program and connect workers to needed services. Fisk argues that hiring halls could spark the growth of sectoral representation by being the center of training and education in employment statutes and negotiation tactics, and provide the structure needed for direct actions.

Exclusive hiring halls, ones in which an employer is required through a collective bargaining agreement to not hire from a source other than the hiring hall, are more effective in solidifying worker power than nonexclusive hiring halls, where the hiring hall is one of many sources of employees. In both cases, hiring halls cannot deny employees access regardless of union membership, but can charge nonmembers a reasonable fee.

Fisk touts the Culinary Union in Las Vegas’s hiring hall as providing great benefits to its users and has contributed to the union’s growth of power. However, this hiring hall as well as other successful hiring halls are run by unions that are the workers’ only bargaining representative once hired, which would not always be the case if hiring halls were to be expanded. If a hiring hall were to be instituted outside the context of a union collective bargaining agreement, there would have to be a statutory or contractual mechanism to either require or incentivize employers to use the hiring hall to fill staffing needs. Such requirements or incentives could be built into public contracting requirements. Other incentives or requirements that could support hiring halls include:

- Passing a statute which exempts companies from certain minimum labor standards laws if companies agree to use a worker-controlled co-operative system for hiring. Fisk argues that passing a statute like this would incentivize companies, particularly app-based gig companies that are seeking exemptions from laws like California’s AB 5, to use hiring halls.

- Expanding pre-hire agreements to non-construction industries that employ workers for a short period of time like agriculture and other seasonal work. Currently only construction trades unions have pre-hire agreements with contractors in which they negotiate collective bargaining agreements before hiring so that the contractor can access the union hiring hall. This aids in the quick job matching and rematching of temporary work.

- Encouraging closed-shop agreements for industries in which there is a stable employer base but the demand for labor fluctuates slightly. In a closed-shop agreement, both employers and workers looking for work must go through the hiring hall for hiring purposes.

- Ensuring that worker groups setting the price of services and terms of labor will not be considered an antitrust violation. Unionized hiring hall relationships and collective bargaining agreements currently raise no antitrust issues, so expanding to worker groups should not pose a problem, but if it does, Fisk recommends reforming antitrust law.

- Facilitating negotiation between labor organizations and employers to address the fissurization of work. Fisk argues that hiring hall contracts should be able to follow the work in the case of subcontracting.

- Giving hiring halls the same legal advantages as for-profit employment agencies. Currently unions that operate hiring halls have extensive reporting and disclosure requirements that are not required of employment agencies.

Fisk also proposes that with legal changes in the regulation of unions and benefit plans, hiring halls could assume functions like benefit administration and co-enforcement. She suggests that governments either fund hiring halls directly or require government-funded and public-sector employers to use hiring halls. Additionally, employers would pay fees to hiring halls to support the cost of training and other operations. Fisk recognizes the discriminatory history of hiring halls, and in response demands that hiring halls operate in low-income communities, that a diverse group of elected members monitor for any possible discrimination, and that all hiring halls be covered by anti-discrimination laws and are enforced by government agencies. To ensure the coverage of all workers, Fisk recommends that hiring halls include independent contractors, domestic workers, and other workers not covered under the NLRB.

Conclusions

Labor organizing and the nature of work have fundamentally changed over the last several decades. So, too, must laws change that support sustainable worker organizing and a new movement of sectoral bargaining that is Alt-Labor. Policymakers should consider co-enforcement and legal support for hiring halls as ways to create structures that allow for the continued improvement of working conditions. The COVID-19 crisis has further revealed this need. The economic health of the country and the physical health of the workforce during and after the pandemic will be improved if workers are given a voice and power. Alt-Labor organizing offers a way forward.

FEATURED RESEARCH

Fisk, C. (2020). Sustainable Alt-Labor. Chicago-Kent Law Review 94(1).

ABOUT IRLE’S POLICY BRIEF SERIES

IRLE’s mission is to support rigorous scholarship on labor and employment at UC Berkeley by conducting and disseminating policy-relevant and socially-engaged research. Our Policy Brief series translates academic research by UC Berkeley faculty and affiliated scholars for policymakers, journalists, and the public. To view this brief and others in the series, visit irle.dream.press/publicationsSeries editor: Lori Ann Ospina, Associate Director of IRLE