The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is now the primary anti-poverty program in the U.S., but it has not kept up with wage stagnation. Berkeley faculty recently proposed an increase in the federal EITC, California has adopted an expansion of its own state EITC, and Congress passed a tax bill that fails to help EITC recipients.

Overview

With the dismantling of many federal safety net programs, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is now the major federal anti-poverty program.1 Some states have enacted their own EITC programs, but state credits are much smaller. While states like California have adopted increases to the EITC over time, the maximum federal EITC for families with two or fewer children has not changed significantly since the 1990s.

IRLE faculty affiliates Hilary Hoynes and Jesse Rothstein and Berkeley graduate student Krista Ruffini propose to expand the federal EITC. They show that a 10 percent across-the-board increase in the credit would help lift hundreds of thousands more out of poverty at a time when wages have stagnated for workers in the bottom half of the income distribution. Their proposal responds to growing empirical research on the benefits of the EITC.

California adopted a modest expansion to its state-level EITC in 2017: increasing the income cap and extending the credit to self-employed workers previously ineligible for the EITC.2 The value of the credit was unchanged.

How the federal EITC works

The EITC is a federal tax credit for low-income earners. The amount of the credit depends on family structure and total family income.3 The EITC is refundable: if a family’s credit exceeds their tax obligation, they receive a check.

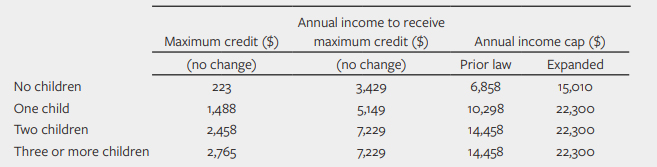

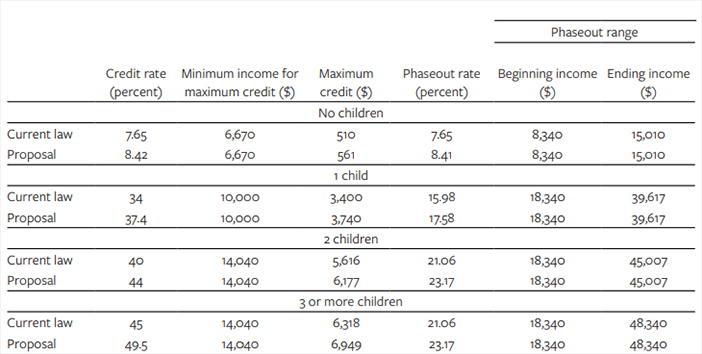

Eligibility for the credit phases out at certain income thresholds: in 2017, single taxpayers with incomes up to $39,617 (with one child), $45,007 (with two children), or $48,340 (with 3 or more children) were eligible for the credit (see Table 1). Income caps for married filers are higher than for single taxpayers.4

The EITC can be as high as 45% of a family’s pre-tax income.5 In 2017 the maximum credit was $6,318 for families with 3 children, $5,616 for families with 2 children, $3,400 for families with 1 child, and $510 for working individuals without children (see Table 1).

Overdue for a change

From its establishment in 1975 through 1993, the federal EITC did not vary based on the number of children in a family and was not available to low-wage workers without children. In 1993 the EITC increased significantly for families with two or more children and was extended to workers without children.

In 2009 the EITC was raised for workers with three or more children, as part of the federal economic stimulus package. Apart from these changes, the real value of the EITC has largely remained stagnant.6

A new proposal

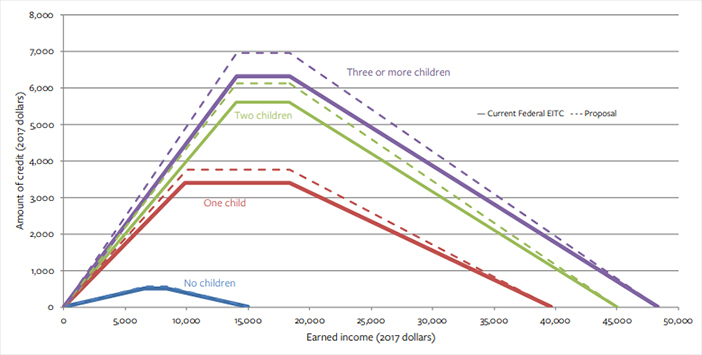

In a proposal written for the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institute, IRLE faculty affiliates Hilary Hoynes and Jesse Rothstein, along with UC Berkeley doctoral student Krista Ruffini, recommend a 10 percent across-the-board increase in the amount of the federal EITC.7 For families with fewer than three children, the federal credit has been frozen in inflation-adjusted terms since 1996, and an increase would greatly offset the effects of wage stagnation experienced by workers at the low-end of the income distribution.

Hoynes et al estimate that such an increase would lift roughly 600,000 individuals, including 300,000 children, out of poverty annually. The proposed increase would benefit families who are below 300 percent of the poverty line, with the largest benefits going to workers earning between $10,000 and $30,000 a year.

How the proposal would work

The income eligibility structure of the credit would be maintained, but all recipients of the credit would see a 10 percent across-the-board increase. For a worker with no children, the maximum credit would rise from $510 to $561. The maximum credit for workers with children would increase by up to $631, depending on the number of children in a given family. Proposed changes to the EITC schedule are shown below in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Low-income workers who live in a state with an EITC would continue to receive the same state credit, as well as an increase in their federal credit. State credits are typically much smaller than the federal credit and credit amounts vary widely from state to state. For example, for families with at least three children, Louisiana’s credit is just 3.5 percent of the amount of the federal credit, and Wisconsin’s is 45 percent of the federal credit. The increase proposed by Hoynes, Rothstein, and Ruffini is comparable to the average credit amount of the state-level EITC add-ons in many states.

Hoynes, Rothstein, and Ruffini estimate that the proposal would cost the U.S. Treasury about $7.0 billion a year, roughly 10 percent of current EITC expenditures. The authors point out that the incomes of high earners have far outpaced those at the bottom of the income distribution.8 To account for this imbalance and to pay for the credit increase, Hoynes et al suggest raising tax rates on high-income earners or limiting tax loopholes and deductions that benefit the highest-income earners.

2017 Federal tax changes

The 2017 federal tax bill failed to expand the EITC, and instead made several changes that will benefit high earners and negatively affect the lowest earners and larger families.

The federal tax bill made no direct changes to the EITC. However, the bill adopted the “chained” Consumer Price Index, a slower-adjusting measure of inflation, for calculating the value of the EITC. This measure will cause the maximum EITC to rise more slowly over time, resulting in smaller credits, especially for families with children.9

The bill also expands the Child Tax Credit (CTC) to higher-income earners. Unlike the EITC, the CTC does not reach the lowest earners because it is not fully refundable. Originally created to help low-income families, in 2017 the CTC had income phase-out limits for single filers earning $75,000 and married taxpayers filing jointly earning $110,000.10 After the tax reform bill was passed, single filers earning up to $200,000 and married couples earning up to $400,000 can now claim the CTC.11

Congress doubled the maximum amount of the CTC from $1,000 to $2,000 for children under age 17. But the tax bill also eliminates personal exemptions, which for families over four may cancel out any value of the CTC increase. An analysis by the Brookings Institute Tax Policy Center shows that single and married couples earning $30,000 a year—either with or without children—may end up paying more in taxes by 2027.12

Federal efforts to increase the EITC

In September 2017, Representative Ro Khanna (D-CA) and Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) introduced the Grow American Incomes Now (GAIN) Act, which would significantly increase the federal EITC for low-wage workers, and extend it to more middle-class workers by raising the income limits. The proposal doubles the maximum amount of the EITC for workers with children, and increases the EITC for childless workers nearly six-fold.13

The proposal would also extend the credit to individuals making up to $76,000 per year who have three or more children (up from the current cap of $48,340).

The last action taken on the GAIN Act was in September 2017, when the bill was referred to the House Committee on Ways and Means.

Research on EITC’s success

- Together with the Child Tax Credit (CTC), the EITC has become the bedrock of anti-poverty programs, particularly for families with children. In 2015 alone, the credit helped move 9.2 million people, including 4.8 million children, out of poverty.14

- Hoynes and Patel (2015) found that the 1993 expansion of the EITC increased employment for single working mothers with less than a college degree by 6.1 percentage points.15

- In 2013, the EITC reached nearly 20 percent of all tax filers—or roughly 29 million people—with an average credit of $3,063 for families with children.16

- 44 percent of tax filers with children receive the EITC.17

- Hoynes and colleagues (2015) found that the 1993 expansion of the EITC resulted in reduced rates of low birth weight. An additional $1,000 EITC during pregnancy resulted in reducing rates of low birth weight by 7 percent overall, and reduced low birth rates by 8.2 percent among African Americans.18

- Dahl & Lochner (2017) found that an additional $1,000 EITC payment leads to a modest increase in standardized

test scores for school-aged children.19

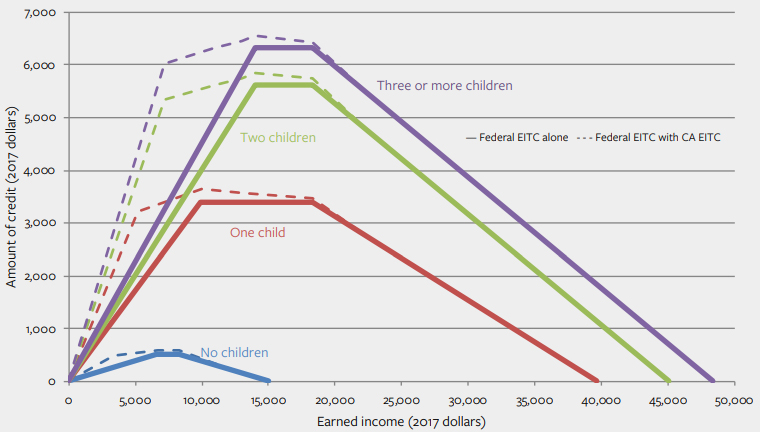

FIGURE 1 Current Federal EITC and Proposed Increase, Tax Year 2017 (single and head of household)

Source: Authors’ calculations.

TABLE 1 Current Federal EITC and Proposed Increase, Tax Year 2017 (single and head of household)

Source: Hoynes, Rothstein & Ruffini (2017).

Conclusion

While the federal tax reform bill transformed the existing tax structure, many of the changes are unlikely to benefit low-income families. Two proposals to modify the EITC are on the table to improve salaries for those at the lower end of the income distribution. Both the GAIN Act and the proposal put forward by Hoynes, Rothstein, and Ruffini to increase the federal EITC build on decades of empirical research revealing strong benefits for working-class families to increase earnings and help them stay out of poverty.

In the meantime, progress can be made at the state level, where states with EITC add-ons can increase the credit value or consider extending the credit to a broader pool of workers, as in the case of California.

While the EITC has become the trademark anti-poverty program in the U.S., Hoynes, Rothstein, and Ruffini also suggest that policymakers invest in other policies that intervene in market outcomes directly to further support low-income workers and families. They suggest raising the minimum wage, and providing affordable childcare and paid family leave to encourage labor force attachment and to increase take-home pay for low-wage Americans.

California’s 2017 EITC expansion

California—along with 26 other states and the District of Columbia—has its own EITC to provide for credits on state

income taxes.20 Adopted in 2015, California’s EITC in 2017 has a maximum credit of $2,458 for families with two children.21 The California credit phases out at a much lower income threshold than the federal EITC for filers with children (see Table 2).California’s EITC credit reached 360,000 recipients each year since it was established in 2015. In 2016 the legislature

passed an expansion of the credit with two changes: (1) increasing the credit’s income eligibility limits to higher-income earners and (2) extending eligibility to self-employed workers.22 The credit is now available to single filers without children earning up to $15,010, and to workers with children making up to $22,300.23 The credit amount (which increases every year with inflation) was not changed.

The California Budget and Policy Center estimates that these changes will extend the credit to over one million additional low-income workers beginning in tax year 2017.

TABLE 2 California EITC Under Prior Law v. 2017 Expansion 24

Source: Weatherford (2017).FIGURE 2 Current Federal EITC with California Expansion

FEATURED RESEARCH

Hoynes, H., Rothstein, J., & Ruffini, K. (2017). “Making work pay better through an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit.” Washington, DC: Brookings Institute. http://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/making_work_pay_expanded_eitc_Hoynes_Rothstein_Ruffini.pdf

OTHER IRLE POLICY BRIEFS ON THE EITC

Hoynes, H. (2017). “The Earned Income Tax Credit: A key policy to support families facing wage stagnation.” Berkeley, CA: Institute for Research on Labor and Employment. http://irle.dream.press/the-earned-income-tax-credit-a-key-policy-to-support-families-facing-wage-stagnation/

Nichols, A. & Rothstein, J. (2015). “The Earned Income Tax Credit.” Berkeley, CA: Institute for Research on Labor and Employment. http://irle.dream.press/the-earned-income-tax-credit-wp/

Montialoux, C. & Rothstein, J. (2015). “The new California Earned Income Tax Credit.” Berkeley, CA: Institute for Research on Labor and Employment. http://irle.dream.press/the-new-california-earned-income-tax-credit/

ABOUT IRLE’S POLICY BRIEF SERIES

IRLE’s mission is to support rigorous scholarship on labor and employment at UC Berkeley by conducting and disseminating policy-relevant and socially-engaged research. Our Policy Brief series translates academic research by UC Berkeley faculty and affiliated scholars for policymakers, journalists, and the public. To view this brief and others in the series, visit irle.dream.press/policy-briefs/

Series editor: Sara Hinkley, Associate Director of IRLE

References

- See the following IRLE policy briefs for research on the effectiveness of the EITC: Montialoux, C. & Rothstein, J. (2015). The New California Earned Income Tax Credit. Berkeley, CA: IRLE. http://irle.dream.press/the-new-california-earned-income-tax-credit/ and Hoynes, H. (2017). The Earned Income Tax Credit: A key policy to support families facing wage stagnation. Berkeley, CA: IRLE. http://irle.dream.press/the-earned-income-tax-credit-a-key-policy-to-support-families-facing-wage-stagnation/

- See for example: Montialoux, C. & Rothstein, J. (2015). Anderson, A. (2017). Expanded CalEITC is a major advance for working families. Sacramento, CA: California Budget & Policy Center. http://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/expanded-caleitc-major-advance-working-families/

- Nichols, A. & Rothstein, J. (2015). “The Earned Income Tax Credit.” Berkeley, CA: Institute for Research on Labor and Employment. http://irle.dream.press/the-earned-income-tax-credit-wp/

- For married or joint filers in tax year 2017, those with combined income of $20,600 without children are eligible for the credit. For joint filers with one child, the income limit is $45,207; for those with two children, the income limit is $50,597; and for those with three or more children the income limit is $53,930. For more information, see: Internal Revenue Service (2018). 2017 EITC income limits, maximum credit amounts and tax law updates. https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/earned-income-tax-credit/eitc-income-limits-maximum-credit-amounts

- Hoynes, H. (2017).

- Only the phase-out income thresholds are adjusted annually for inflation. For more, see: Falk, G., & Crandall-Hollick, M.L. (2016). “The Earned Income Tax Credit: An overview.” Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43805.pdf

- Hoynes, H., Rothstein, J., & Ruffini, K. (2017).

- See for example: Picketty, T., & Saez, E. (2016). Income inequality in the United States, 1913-1998. Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(1), 1-39.

- Marr, C. (2017, December 21). Instead of boosting working-family tax credit, GOP Tax Bill erodes it over time. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/blog/instead-of-boosting-working-family-tax-credit-gop-tax-bill-erodes-it-over-time

- DePillis, L. (2017, December 16). Changes to the child tax credit: What it means for families. CNN Money. http://money.cnn.com/2017/12/16/news/economy/child-tax-credit/index.html

- DePillis, L. (2017).

- Tax Policy Center (2017). Effects of Tax Cuts and Jobs Act on representative families. Washington, DC: Urban Institute & Brookings Institution. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/publication/150671/2001638-effects_of_the_tax_cuts_and_jobs_act_on_representative_families_0.pdf

- Office of Congressman Ro Khanna (September 13, 2017). Release: Sen. Sherrod Brown and Rep. Ro Khanna introduce landmark legislation to raise the wages of working families. https://khanna.house.gov/media/press-releases/release-sen-sherrod-brown-and-rep-ro-khanna-introduce-landmark-legislation

- Hoynes, H. (2017).

- Hoynes, H. & Patel, A. J. (2015).

- Hoynes, H. & Rothstein, J. (2016). Tax Policy Toward Low-Income Families. Working Paper 22080. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Hoynes, H. & Rothstein, J. (2016)

- Hoynes, H., Milles, D.L., & Simon, D. (2015). Income, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Infant Health. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 7(1), 172-211.

- See the following: Dahl, G. B., & Lochner, L. (2010). The impact of family income on child achievement: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit. CIBC Centre for Human Capital and Productivity. CIBC Working Papers, 2010-5. London, ON: Department of Economics, University of Western Ontario. Dahl, G. B., & Lochner, L. (2017). The impact of family income on child achievement: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit: Reply. American Economic Review, 107(2), 629-31.

- Hoynes, H., Rothstein, J., & Ruffini, K. (2017).

- Weatherford, B. (2017). California’s Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) expansion. Sacramento, CA: Legislative Analysts Office. http://www.lao.ca.gov/LAOEconTax/Article/Detail/249

- Anderson, A. (2017).

- Weatherford, B. (2017).

- All numbers calculated for 2017 tax year; assumes 2.1 percent inflation adjustment. Prior law EITC income includes only wages subject to withholding.