An up-to-date picture of COVID-19’s labor market impact is now available, thanks to researchers at IRLE, the California Policy Lab, Rustandy Center for Social Sector Innovation at Chicago Booth, and the University of Chicago Poverty Lab. They are taking advantage of granular data on exact hours worked among employees of firms that use the Homebase scheduling software. Check back for updates:

Post Seven: Labor Market Recovery Stalls as COVID-19 Cases Surge

Post Six: Measuring the Labor Market Since the Onset of the COVID-19 Crisis (August 3)

Erratum: Corrected estimates of layoff and hours changes in Homebase data

Post Five: Update with Homebase Data Through May 23

Post Four: Update with Homebase Data Through May 9 and Description of Homebase Firm Characteristics

Post Three: Update with Homebase Data Through April 25

Post Two: Update with Homebase Data Through April 11

Post One: Initial Analysis of Data Through March 28 and Methodology

Erratum: Corrected estimates of layoff and hours changes in Homebase data

We recently discovered an error in our analyses of employment changes in the Homebase data. We are grateful to Lucas Finamor for bringing it to our attention.

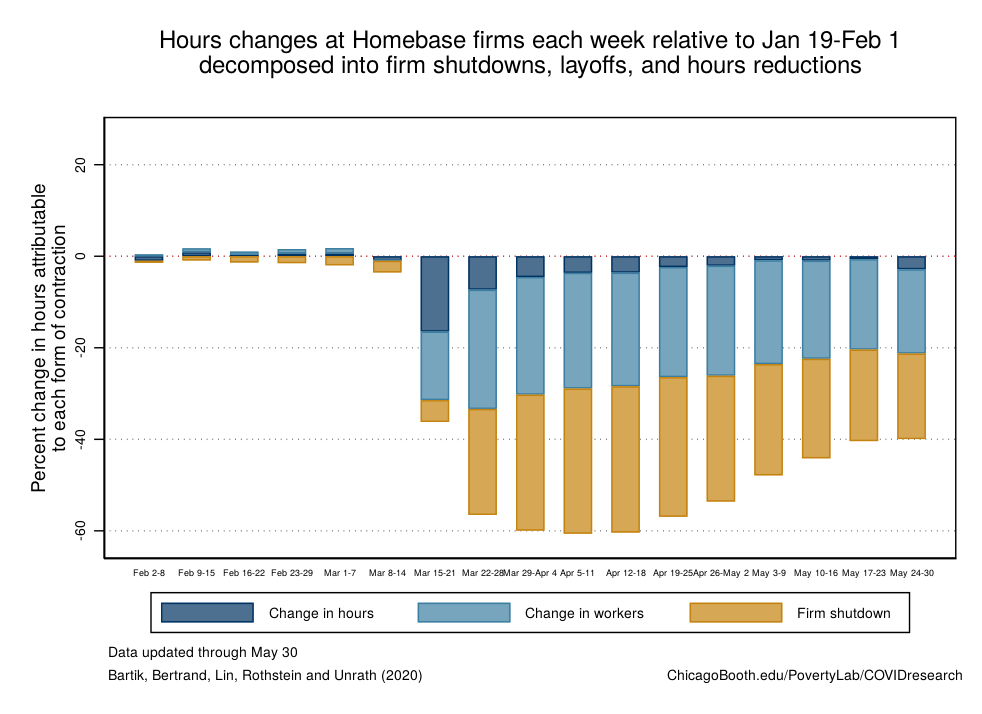

The error only affects our analysis of the relative importance of changes in the number of workers and changes in average hours worked at firms that remained open. Our old estimates overstated the importance of hours changes and understated the impact of layoffs. We present here corrected estimates.

Overall hours worked at Homebase firms fell by 60% between the baseline period of Jan 19-Feb 1 and the week of April 5-11. As before, we find that the majority of this decline came from firms that closed entirely – that had no hours registered at all with Homebase during the week of April 5-11. We then decompose the remaining change in hours, around 28% of baseline, into a component coming from changes in the number of employees (counting only those with positive hours in the week) and a component coming from changes in average hours worked per remaining employee. Our earlier releases indicated that of these two, hours per worker played by far the larger role, but that was an error. Our corrected results, shown in Figure 1, indicate that hours reductions played a meaningful role in March 15-21, when they may have reflected workers who were laid off mid-week, but that thereafter reductions in firm headcounts were by far the dominant component.

This correction resolves an inconsistency with results reported by Cajner et al. (2020) from payroll records, which show substantial layoffs from continuing businesses.

This is more pessimistic news for the prospect of a quick recovery, as workers who have been separated may be less likely to be recalled than workers whose hours are cut but who remain attached to the employer. As we look at the weeks since the nadir, and consistent with this grimmer picture, the recovery has been driven more by reopenings of previously closed firms than by recall of laid off workers. The error does not affect our previous finding that firms that have reopened have largely done so by recalling their former workers rather than by bringing on new employees, suggesting that temporary dis-attachment need not be permanent. This will be an important margin to track going forward.

Authors

Alexander W. Bartik, Assistant Professor Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and Research Affiliate, UChicago’s Poverty Lab

Marianne Bertrand, Chris P. Dialynas Distinguished Service Professor of Economics, University of Chicago Booth School of Business, and Faculty Director, Chicago Booth’s Rustandy Center for Social Sector Innovation and UChicago’s Poverty Lab

Feng Lin, Research Professional, Chicago Booth

Jesse Rothstein, Professor of Public Policy and Economics, University of California, Berkeley, and Director, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment (IRLE) and California Policy Lab

Matt Unrath, PhD Candidate, Goldman School of Public Policy, UC Berkeley, and Research Fellow, California Policy Lab

Acknowledgments

We thank Homebase and Ray Sandza in particular for generously allowing access to their data and sharing their time to answer questions and help us understand the data. We also thank Jingwei Maggie Li, Salma Nassar, and Greg Saldutte at Booth’s Rustandy Center for Social Sector Innovation and Manal Saleh at the Poverty Lab for excellent assistance on this project and Michael Stepner for comments.