People who have been arrested, convicted of a crime, or incarcerated face many barriers to employment. While much of the difficulty in finding employment is due to institutional exclusion, a UC Berkeley researcher has attributed some of the problem to ineffective job search methods. What can policymakers do to ensure that people who have interacted with the carceral system can find employment?

Overview

High rates of unemployment among the formerly incarcerated serve to extend punishment long after time has been served. Much of the difficulty in finding a job comes from institutional exclusion, but the search methods jobseekers employ also pose obstacles to their success. UC Berkeley sociologist Sandra Susan Smith has found that the system-involved are less likely to search for jobs, and those who do use less effective search methods. Policies that might improve these outcomes include creating resource guides on best practices for employment as well as expanding post-release employment programs. Expanding expungement, Ban the Box/Fair Chance legislation, and employer hiring incentives can also help overcome institutional barriers to employment for those exiting the carceral system.

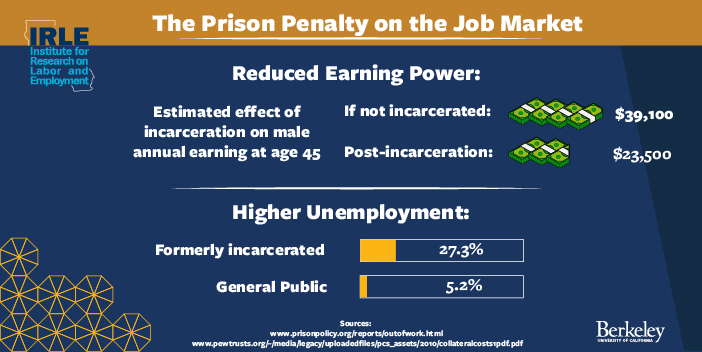

High Unemployment for the System-Involved

Over the last 40 years, the incarceration rate in America has skyrocketed.1 Today, one in three people in the United States have had contact with the carceral system.2 Despite its prevalence, having a criminal record continues to make finding employment extremely difficult. The formerly incarcerated have an unemployment rate of 27% (compared to under four percent for the entire U.S. population).3 Additionally, those who are able to find employment are more likely to earn lower wages and work fewer weeks.4 The issue is especially pronounced for people of color, who are also more likely to be arrested, found guilty, and severely punished.5

The carceral system ostensibly aims to hold people accountable for crimes they have committed and reform them to reenter and productively contribute to society. However, when the system-involved (which for the purposes of this brief is defined as everyone who has been arrested, convicted, or incarcerated) are unable to find jobs, the cycle of poverty and recidivism is perpetuated. Employment not only helps people who are formerly incarcerated stay out of prison, but it also improves the economy.6 Employment barriers for those with criminal backgrounds result in an estimated loss to the country of between $78 and $87 billion in annual gross domestic product.7

There are many factors that lead to high rates of unemployment and detachment among the system-involved. Much of this is institutional exclusion in the form of state and federal restrictions to employment and employers’ distrust of applicants who have a criminal background. In two papers, UC Berkeley sociologist Sandra Susan Smith looks at the supply side of unemployment among the system-involved, including whether or not people with a criminal record search for work, what search strategies are used, and how willing contacts of the formerly incarcerated are to provide assistance in finding a job.

The Decision to Search

In a new paper, Smith and Nora C.R. Broege of Rutgers University, Newark, analyze 11 years of a national longitudinal study to examine whether contact with the carceral system alters job search strategy for Black, Latino, and white men.8 Because of the massive institutional exclusion and structural barriers to employment faced by the system-involved, Smith and Broege wanted to study how and how much they search for jobs. The researchers find that after contact with the carceral system, people were less likely to search for work, leading to detachment, and those that did search for work used less effective search methods, often leading to unemployment.

Smith and Broege find that arrest and incarceration reduce the odds of job search by 57% and 53%, respectively, relative to if those individuals were searching for jobs before contact with the carceral system. Researchers have found that for the general public, the decision whether or not to search for jobs is affected by three factors: the quantity and quality of open positions, the quality of the individual’s options before they started searching, and the opportunities that the individual has to search.9

For those that have had contact with the carceral system, government-imposed restrictions, employer discrimination, and lack of opportunities in their communities severely limit the quantity and quality of positions available. In addition, large debt liabilities from legal financial obligations such as fees and restitution can actually discourage job search because of how burdensome the debt is, particularly for Black and brown communities who receive more severe penalties. The financial stress from these obligations counterintuitively reduces search efforts and ability to commit to work, and those in debt turn to crime or cash assistance instead of work because of the paralyzing effect of the debt.10

Furthermore, court obligations such as community service, drug testing, and meetings with parole officers disrupt the job search process.

Successful Search Methods

Smith and Broege distinguish which job search methods are most effective for the system-involved population compared to their pre-contact search success. For the general population, network search, direct application, and labor market intermediation (such as temporary employment agencies) are considered to be the most efficient and effective search methods.11

While other research suggests that personal networks are one of the quickest ways that formerly incarcerated individuals find work, Smith and Broege find that carceral contact significantly decreases the odds of network search, and that the effectiveness of this strategy varies significantly by race. Personal network search increases the probability of success for whites by 13 percentage points, but for Black and Latino men, network search lowers the probability of search success by 14 and 15 percentage points. In a 2018 paper, Smith interviewed 126 jobholders at a large public sector employer and found that even when the formerly incarcerated have social capital to try to network search, they often face difficulties mobilizing their networks. Smith observes that even when jobholders have the ability to refer people they know that are system-involved to available jobs at their workplace, they often do not because they want to see a signal that the former prisoner has “changed” or is committed to not re-offending.12

Smith and Broege find that the system-involved are significantly more likely to use a labor market intermediator and less likely to apply directly to employers.

The researchers confirm that carceral contact significantly increases the use of passive search methods like placing and responding to ads, likely because applicants are attempting to avoid employer bias. Yet using these search methods actually reduces search success.

Smith’s research suggests that people who have had contact with the carceral system need to change their job search methods. However, given state, federal, and private restrictions on access to employment and employers’ and networks’ general distrust of people who have been involved with the carceral system, the following policy changes need to be made in addition to providing resources to assist in the job search process.

Recommendations

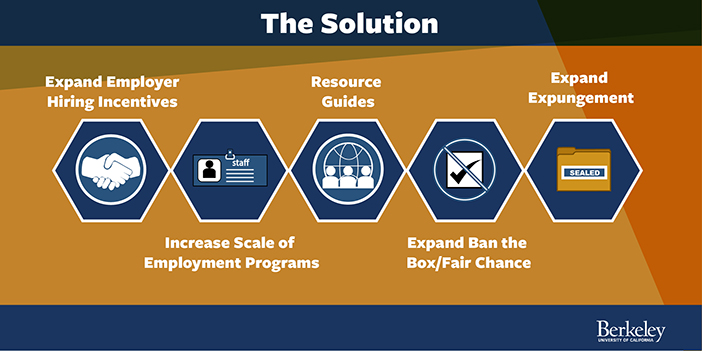

Create State Resource Guides

“Roadmap to Reentry: A California Legal Guide,” published by Root & Rebound, is a resource for the major barriers to reentry for people in California, covering employment, housing, education, parole, and more.13 The guide gives tips on looking for work and applicant’s rights regarding background checks. States should fund state-specific guides for people preparing for release, increasing their chances of finding employment.

Fund Transitional Employment Programs

While some studies have shown that employment programs do not affect employment, Bushway and Appel find that these programs play a crucial role by signaling to employers (and networks) that the graduates are less likely to recidivate and are more productive.14 In one focus group, 90% of employers reported that completing a transitional program after release would favorably impact their hiring decision.15

Expand Expungement

Expungement is the sealing of criminal records so that the record is no longer accessible to the public, including employers. While there have been few studies on the impact that expungement has on wages and employment for the system-involved, the results available are promising. Researchers at Berkeley Law found that people who participated in a record clearing program had higher employment rates and higher earnings compared to before their records were sealed.16 Over the last few years, several states have broadened eligibility for expungement (including sealing non-conviction records), shortening the time period and automating the process.17

For example, under current California law, those convicted of misdemeanors or low-level felonies must formally request to have their records sealed. Legislation recently proposed in the California State Assembly would automatically seal these records after sentence completion.18 Expanded expungement would increase opportunities and reduce the potential for employer discrimination.

Consider Expanding Ban the Box/Fair Chance

Ban the Box is a campaign to prohibit forms that ask applicants to check a box if they have a criminal record.19 Such a prohibition has been adopted by 33 states and over 150 cities and counties.20 Some laws, like the Fair Chance Act in California, also delay background checks until a conditional offer has been made. If an employer is reviewing conviction history after the conditional offer has been made, they must conduct an individualized inquiry that considers a variety of factors about the conviction before they can rescind the offer. If an applicant is denied a job because of this inquiry, they must receive notice of the reasoning and they have the right to appeal the decision.21

More jurisdictions should consider passing Ban the Box or Fair Chance legislation, and expansions to cover private and public employers and educate applicants on their rights and the appeals process. However, while Ban the Box does increase callback rates for people with criminal records, recent research has shown that it also serves to reduce the likelihood that young Black and Latino men will receive callbacks because employers stereotype who they believe will have criminal records. These unintended consequences of the policy can be addressed by improving equal employment legislation, and reducing racially identifying information on applications.22

Expand Employer Hiring Incentives

The Work Opportunity Tax Credit provides a tax credit to employers of up to $9,600 for each formerly incarcerated employee. The credit has low take-up due to administrative burden and a lack of employer awareness. Research has shown that the program increases wages and provides other positive labor market outcomes. Other policies like Promise Zones and Enterprise Zones, which focus tax benefits in high-poverty areas, also show evidence of improved labor market conditions.23 Policymakers should expand these incentives and pursue strategies for improving their implementation.

FEATURED RESEARCH

Smith, S. (2018). ‘Change’ frames and the mobilization of social capital for formerly incarcerated job seekers. Du Bois Review.Smith, S.S. & Broege, N.C. (2019). Searching for work with a criminal record. Social Problems, forthcoming.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Collateral Consequences Resource Center: a non-profit that promotes the discussion of the many consequences that the system-involved face from having a criminal record. http://ccresourcecenter.org/National Employment Law Center: an organization that researches and advocates for Fair Chance and Ban the Box policies. https://www.nelp.org/campaign/ensuring-fair-chance-to-work/

Prison Policy Initiative: a non-profit research and advocacy organization that focuses on exposing the harm of mass criminalization. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/

Root & Rebound: a reentry advocacy center whose programs and resources aim to equip those going through reentry and those that support them with tools for successful reintegration. http://www.rootandrebound.org/

NOTE

The language used in this brief aims to put the identity of the system-involved as people first. For more information, please see the UC Berkeley Underground Scholars Initiative Language Guide, found here: https://undergroundscholars.berkeley.edu/news/2019/3/6/language-guide-for-communicating-about-those-involved-in-the-carceral-system.ABOUT IRLE’S POLICY BRIEF SERIES

IRLE’s mission is to support rigorous scholarship on labor and employment at UC Berkeley by conducting and disseminating policy-relevant and socially-engaged research. Our Policy Brief series translates academic research by UC Berkeley faculty and affiliated scholars for policymakers, journalists, and the public. To view this brief and others in the series, visit irle.dream.press/policy-briefs/Series editor: Sara Hinkley, Associate Director of IRLE

References

- Pfaff, J.F. (2012). The causes of growth in prison admissions and populations. Available at https://web.law.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/microsites/criminal-law-roundtable-2012/files/Pfaff_New_Admissions_to_Prison.pdf

- Friedman, M. (2015, November 17). Just facts: As many Americans have criminal records as college diplomas. Brennan Center for Justice. Retrieved from https://www.brennancenter.org/blog/just-facts-many-americans-have-criminal-records-college-diplomas.

- Couloute, L. & Kopf, D. (2018, July). Out of prison & out of work: Unemployment among formerly incarcerated people. Prison Policy Initiative. Retrieved from https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/outofwork.html.

- Freeman, R. (1991). Crime and the employment of disadvantaged youths. Working Paper No. 3875, National Bureau of Economic Research.; Grogger, J. (1992). Arrests, persistent youth joblessness, and black/white employment differentials. Review of Economics and Statistics 74:100-6.; Waldfogel, J. (1994). The effect of criminal conviction on income and the trust ‘Reposed in the Workment.’ Journal of Human Resources 29:62-81.; Waldfogel, J. (1994). Does conviction have a persistent effect on income and employment? International Review of Law and Economics 14:103-19.; Nagin, D. & Waldfogel, J. (1995). The effects of criminality and conviction on the labor market status of young British offenders. International Review of Law and Economics 15:109-26.; Western, B. (2006). Punishment and Inequality in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Couloute & Kopf, 2018; Harris, A., Evans, H., & Beckett, K. (2011). Courtesy stigma and monetary sanctions: Toward a socio-cultural theory of punishment. American Sociological Review 76(2): 234-64.; Kutateladze, B.L., Andiloro, N.R., Johnson, B.D., Spohn, C.C. (2014). Cumulative disadvantage: examining racial and ethnic disparity in prosecution and sentencing. Criminology 52(3): 514-551.; Leslie, E. & Pope, N.G. (2017). The unintended impact of pretrial detention on case outcomes: evidence from New York City arraignments. The Journal of Law and Economics 60(3). 529-57.; Pager, D. (2003). The mark of a criminal record. American Journal of Sociology 108(5): 937-975.; Wang, X., Mears, D.P., & Bales, W.D. (2010). Race specific employment contexts and recidivism. Criminology 48(4): 201-241.; Bellair, P. & R. Kowalski, B. (2011). Low-skill employment opportunity and African-American-White difference in recidivism. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 48:176-208.

- Berg, M.T. & Huebner, B.M. (2011, April). Reentry and the ties that bind: An examination of social ties, employment, and recidivism. Justice Quarterly 28(2): 382-410. Available at http://www.pacific-gateway.org/reentry,%20employment%20and%20recidivism.pdf.

- Bucknor, C. & Barber, A. (2016). The price we pay: Economic costs of barriers to employment for former incarcerated individuals and people convicted of felonies. Center for Economic and Policy Research. Available at http://cepr.net/publications/reports/the-price-we-pay-economic-costs-of-barriers-to-employment-for-former-prisoners-and-people-convicted-of-felonies.

- Smith, S.S. & Broege, N.C. (2019). Searching for work with a criminal record. Social Problems, forthcoming. While Smith and Broege only looked at men, it’s crucial to realize that these issues are also prevalent among women, and particularly women of color. Black women that are formerly incarcerated experience a 43.6% unemployment rate, and women of color are the least likely to have a full-time job if they do find a job. (Couloute & Kopf, 2018)

- Brown, D.G. (1965). Academic Labor Markets. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Manpower, Automation, and Training.

- Harris, et al. (2011).; Harris, A., Evans, H., & Beckett, K. (2010). Drawing blood from stones: Legal debt and social inequality in the contemporary United States. American Journal of Sociology 115(6): 1753-99.

- Wielgoz, J.B. & Carpenter, S. (1987). The effectiveness of alternative methods of searching for jobs and finding them: An exploratory analysis of the data bearing upon the ways of coping with joblessness. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 46(2): 151-64.; Blau, D.M. & Robins, P.K. (1990). Job search outcomes for the employed and unemployed. The Journal of Political Economy 98(3): 637-55.; Osberg, L. (1993). Fishing in different pools: Job-search strategies and job-finding success in Canada in the early 1980s. Journal of Labor Economics 11:348-86.; Bishop, J. & Abraham, K.G. (1993). Improving job matches in the U.S. labor market. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Microeconomics 1993(1):335-400.

- Smith, S. (2018). ‘Change’ frames and the mobilization of social capital for formerly incarcerated job seekers. Du Bois Review.

- The guide can be found here: http://www.rootandrebound.org/guides-toolkits.

- Bushway, S.D. & Apel, R. (2012). A signaling perspective on employment-based reentry programming: Training completion as a desistance signal. Criminology & Public Policy 11(1): 21-50. Available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1745-9133.2012.00786.x

- Fahey, J., Roberts, C. & Engel, L. (2006). Employment of ex-offenders: Employer perspectives. Crime and Justice Institute.

- Selbin, J., McCrary, J., & Epstein, J. (2018). Unmarked: Criminal record clearing and employment outcomes criminal law/criminology. The Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 108(1):1-72. Available at https://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3934&context=facpubs.

- Love, M. & Schlussel, D. (2019, January 31). Reducing barriers to reintegration: Fair chance and expungement reforms in 2018. Collateral Consequences Resource Center. Retrieved from http://ccresourcecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Fair-chance-and-expungement-reforms-in-2018-CCRC-Jan-2019.pdf.

- Williams, T. (2019, March 11). Rap sheets haunt former inmates. California may change that. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/11/us/california-criminal-records-bill.html.

- https://bantheboxcampaign.org/

- Avery, B. & Hernandez, P. (2018, September). Bax the box: U.S. cities, counties, and states adopt fair-chance policies to advance employment opportunities for people with past convictions. National Employment Law Project. Available at https://www.nelp.org/publication/ban-the-box-fair-chance-hiring-state-and-local-guide/.

- Ibid.

- Stacy, C. & Cohen, M. (2017, February). Ban the box and racial discrimination: A review of evidence and policy recommendations. Urban Institute. Available at https://www.urban.org/research/publication/ban-box-and-racial-discrimination/view/full_report.

- Looney, A. & Turner, N. (2018, March). Work and opportunity before and after incarceration. Economic Studies at Brookings. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/es_20180314_looneyincarceration_final.pdf.